Optimize Student Performance with Universal Design for Learning

- UDL and performance

- Consider engagement

- Consider presentation of materials

- Consider action and expression

- Conclusion

- Workshop Information

- Resources

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) recognizes that variability exists in student populations along many spectra, and guides the design of learning experiences that present as few barriers to success as possible. The UDL framework is based on the idea that there is no such thing as the average student. For background on the concept of Universal Design for Learning, see the Teaching Resources Page: Reaching All Students with Universal Design for Learning.

This article addresses one of the UDL Guidelines from CAST.org, the leading proponent of UDL. The guideline covered by this article is “Multiple Means of Action and Expression.”

When we begin to apply UDL to an existing course to optimize performance, we start by identifying places where we believe student performance could be improved. Then, we ask ourselves, “Would more flexibility lead to better student performance?” Another way of thinking of this is, might the design of this assessment or assignment favor some individual over others, regardless of their achievement of the learning objectives?

Consider engagement

In the Calvin and Hobbes cartoon (Waterson 1989) at the right, Calvin is explaining to his dad that although he reads well at home, his reading performance in school suffers because “We don’t read about dinosaurs. This cartoon highlights the importance of choice and individual interest in engagement. If we can provide students choice in some aspects of an assessment, they may engage more and perform better.

Engagement is key to performance, so it is important to consider how the nature of an assignment or assessment might affect engagement. In the cartoon at right (source: www.andertoons.com), we see a presenter showing a bar chart and saying to her audience, “I’m not sure what the point of this one is, but there you go.” How engaged would the audience be if they could not see the salience of the content or work to their own goals or the real world? For this reason, authentic assessments that reflect real world problems can help optimize performance.

At left, the cartoon shows ten people milling around a hallway, and every one of them is thinking, “All these people really seem to have it together and I still have no idea what’s going on.” This cartoon represents the need for a sense of belonging and feeling supported for engagement and thus performance. These become even more important when coursework gets really challenging. Enthusiastically welcoming student input and perspectives on course topics as well as explicitly offering support and building community are key to engagement and performance.

Consider presentation of materials

If learners cannot perceive or cannot make sense of materials…particularly the materials directly relevant to an assignment or assessment, their performance will suffer. Helping them make sense of the materials is not about dumbing it down, but rather about making sure it’s very clearly communicated in terms of language and organization.

Quiz and exam questions and assignment instructions and materials must be fully accessible…as should the instructional materials that the assessments are based on…in order to ensure everyone can access them. Images must have alt tags, and videos and audio must have accurate closed captioning. Text and tables must be formatted accessibly as well. You can learn more about digital accessibility in the article, Elevate Your Content with Universal Design for Learning.

When considering clarity and comprehension, it’s important to avoid unfamiliar acronyms and jargon as well as culturally-specific idioms or references. If a learner encounters jargon and culturally specific references they don’t understand, their feelings of belonging may suffer as well, which relates back to engagement. When the ability to define complex terms is not part of an assessment, offering some vocabulary support can be helpful.

Consider a lab activity, performed at a bench, that requires standing for long periods of time while a process runs. A student who can perform the lab tasks might struggle for other reasons…maybe they have difficulty standing for long periods of time. Likewise, a student asked to write an exam in a bluebook might struggle due to an injured hand or arm. Much the like the animals in this cartoon, these students performances would not demonstrate what they can do because there are arbitrary physical obstacles to completing the task.

Consider action and expression

“Learners differ in the ways they navigate a learning environment, approach the learning process, and express what they know.”

CAST.org

Ultimately, performance is about action and expression. When we look at what we are asking students to DO and HOW we want them to do it through a UDL lens, we have to remember that learners differ in the ways they approach the learning process and express what they know.

Support self-regulation

One specific skill that is necessary for optimal performance but is commonly undeveloped in college-aged students is executive function and the related skill of self-regulation. According to a Psychology Today article “Executive function describes a set of cognitive processes and mental skills that help an individual plan, monitor, and successfully execute their goals.” The article goes on to note that much of this functioning relies on the prefrontal cortex region of the brain, and this region of the brain is still developing in college-aged adults. Notably, development of these skills can be more difficult in individuals with some genetic factors as well as childhood trauma. (Psychology Today, n.d.) In a sense, it’s developmentally appropriate for them to struggle with self-regulation.

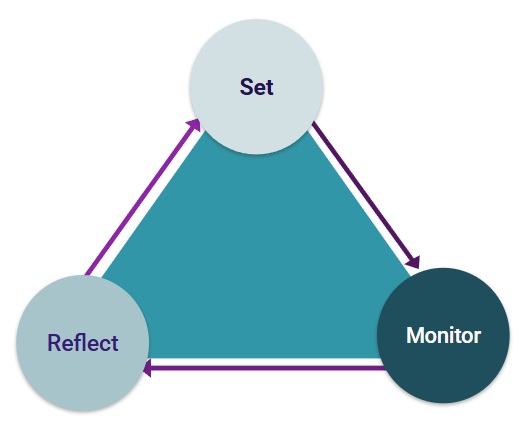

Self-regulation in the context of academic performance means that one can set appropriate goals, monitor their progress toward reaching those goals and adjust along the way, and then reflect on how that process went in order to do a better job the next time.

Self-regulation is important in preparing for an exam, writing a paper (especially one that involves multiple steps) and completing longer-term projects. By scaffolding the self-regulation process, instructors can not only improve performance in their courses but also help students develop this important life skill

Example of how to support self-regulation is breaking down larger projects or papers into steps and establishing milestones. Offering feedback along the way, at each milestone, is also important to help with monitoring.

Learners, especially those who have been highly successful with ease in high school, may not know how to prepare for a major exam that covers more content than they are accustomed to. They may believe that simply reviewing their notes will work. Instructors can help them by talking about how they might be preparing one or two weeks before an exam and helping them develop a study plan. After an exam, instructors can help them work through analysis of their performance and what that might mean for future exams. Some examples of supports are here: Pre-Exam Planner (setting and monitoring) and Post-Exam Analysis and Reflection (reflecting).

Allow for various expression styles and techniques

In the cartoon at left, the instructor offers just one way for a variety of animals (a crow, monkey, penguin, elephant, fish, seal and dog) to prove themselves: climb a tree.

This is a rather extreme and humorous example, but the point is that each of these animals may be in top physical shape and be very strong, but not all of them can express that in the same way. Some arbitrary features of the assessment get in the way of their performance.

Incidentally, asking them to do this one task will likely also lead to disengagement as they might question the relevance of the task and feel like they don’t belong if that is the only measure of evaluation.

Consider communication style & medium

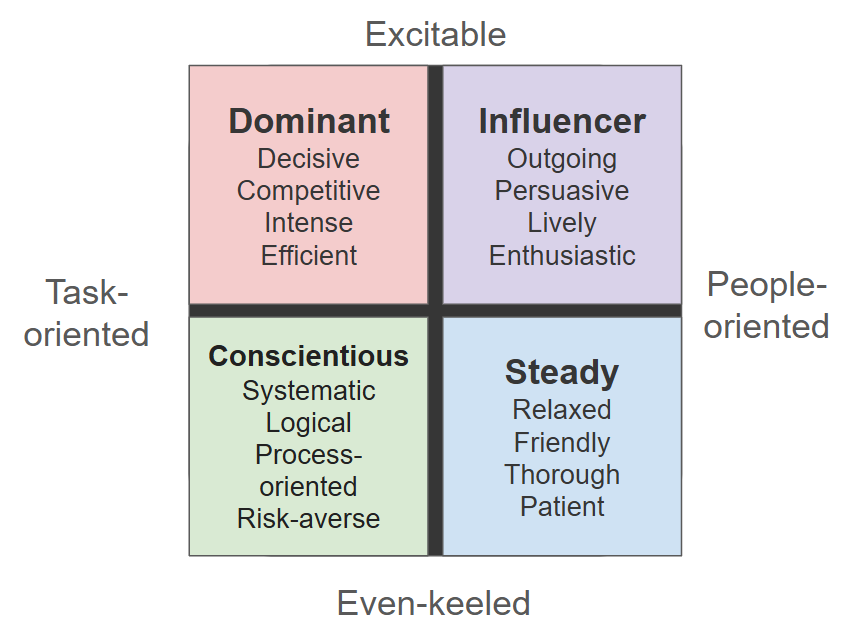

At left is one of many conceptualizations of different communication styles, this one based off the of DISC personality types:

- Dominant, an excitable and task-oriented style. Dominant communicators are described as decisive, competitive, intense and efficient.

- Influencer, an excitable and people-oriented style. Influencers are described as outgoing, persuasive, lively and enthusiastic.

- Steady, a people-oriented and even-keeled style. Steady communicators are described as relaxed, friendly, thorough and patient.

- Conscientious, a task-oriented and even-keeled style. Conscientious communicators are described as systematic, logical, process-oriented and risk-averse.

Another framework for thinking about communication is high-context vs. low-context communication. These are often considered cultural differences, with high-context communicators relying on more indirect, implicit, and non-verbal communication. They are usually more relationship-oriented and focused on the group, and they respect authority and value hierarch. Low-context communicators rely more on direct, explicit and verbal communication. They tent to be more task-oriented and focused on the individual, and they value openness and egalitarianism.

Each classroom likely has a mixture of communication styles, and we can expect that these traits will impact how learners can best express their learning and knowledge. Some might prefer a high-energy debate, while others will shine more if they are given the opportunity to write and revise their thinking thoroughly. On a related note, learners may enjoy or excel at different media for communicating. Some pay enjoy more artistic representations, some may like to write, or speak, discuss, or create a movie.

If the content of the communication is what the learning objective dictates rather than the form or medium, consider if you can allow some flexibility and choice in how students express what they know. Even offering two or three possibilities (rather than opening it up to anything) will allow learners to choose the option that they feel they will excel at.

A common concern about allowing multiple types of submissions is that the grading will be very hard. Will you have to make a separate rubric for each types of assessment? The answer is, “No.” Assuming that a specific communication medium is not a part of the learning objective, your criteria for proficiency is not going to be different – they are dictated by the learning objective.

Below is a possible rubric for evaluating whether a student has mastered a learning objective regardless of how they show this. Note that the rubric evaluates achievement of the learning objective only and also provides choice and flexibility for how that achievement is expressed. For more information on creating and using rubrics see the DELTA Teaching Resources article “Rubric Best Practices, Examples, and Templates.”

| Feedback on how you exceeded this | Proficient achievement | Feedback on room for improvement |

|---|---|---|

| [Description of proficient achievement of criterion 1] | ||

| [Description of proficient achievement of criterion 2] | ||

| [Description of proficient achievement of criterion 3] | ||

| [Description of proficient achievement of criterion 4] | ||

| [Description of proficient achievement of criterion 5] |

Conclusion

By using the UDL framework to ensure that assignments and assessments don’t disengage or demotivate, that the content and instructions are perceivable and comprehendible, and that there is flexibility in how learners take action and express their learning, you can optimize performance. Remember that you don’t have to overhaul every assignment…start with those where you’d like to see improvement in learner performance. Perhaps applying these UDL guidelines will result in the changes you are looking for.

Workshop Information

Optimize Performance with Universal Design for Learning

- Register for an upcoming workshop

- Watch a previously recorded workshop

- Attending this workshop will count toward the Exploring Universal Design for Learning Badge from DELTA.

If no workshops are available, you can request an instructional consultation from LearnTech about this topic.

References and Resources

- CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 3.0. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

- Psychology Today, (n.d.) Executive Function. Retrieved Feb 22, 2023.

- UDL Tips for Assessment from CAST

- DELTA News Article: Alternative Assessment Resources for Teaching and Learning Online

- DELTA News Article: Meet them where they are: Creative alternative assessments