Writing Learning Objectives: Measurable and Mighty

Well-written learning objectives are foundational for effective course design, as they state what the learner will achieve by the end of the class. This article will explore how to apply best practices in order to define expectations for students for a guiding approach.

In this article

- Learning Objectives: A Simple Formula

- How to Choose a Measurable Verb

- Sample Learning Objectives

- Course and Module Objectives

- Assessments

- Resources

Learning Objectives: A Simple Formula

Learning objectives represent the most important outcomes for your course and typically cover a range of levels of student understanding. Each learning objective should be clear and measurable to define what students will be able to do.

To write a learning objective, include two parts:

- Start with a measurable verb. (E.g., “Identify….”)

- Add the knowledge or ability students will apply. (E.g., “Identify the causes and effects of characterization in British literature.”)

How to Choose a Measurable Verb

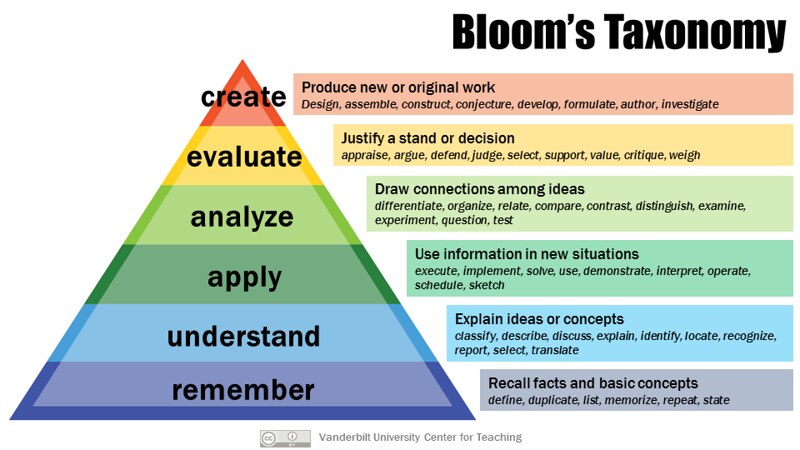

Bloom’s taxonomy classifies six levels of knowledge and skills, spanning lower- to higher-order thinking abilities:

- Remembering, Understanding, Applying, Analyzing, Evaluating, Creating

The pyramid figure is a common visual representation of this taxonomy, although there are many versions of Bloom’s.

Lower-order skills are often necessary first steps that build into higher-order skills. Consider that introductory courses may address skills in remembering, understanding, and applying while intermediate or advanced courses may focus more on analyzing, evaluating, and creating. When choosing verbs, consider which levels of ability are the most suitable for your course.

More extensive Bloom’s Taxonomy lists, including revised and updated versions, offer a broad scope of verbs and coordinating skills for writing learning objectives:

- New Bloom’s Taxonomy (WTCS Foundation)

- A Model of Learning Objectives (Iowa State)

Sample Learning Objectives

The examples below are from a variety of fields:

- Demonstrate appropriate counseling values and attitudes in counseling situations.

- Apply accepted principles and codes to resolve ethical dilemmas that arise in the client/counselor relationship.

- Identify the reagent in a chemical reaction when given the starting material and the ending material.

- Explain how horticulture practices impact bee populations.

- Display insect specimens using appropriate mounting and labeling techniques.

Course and Module Objectives

As you create learning objectives, it’s helpful to consider two levels:

- Course-level objectives, and

- Module- or unit-level objectives, with the latter serving as building blocks to achieve the broader goals.

Course-level objectives describe what students should be able to achieve by the end of the entire course. These objectives are typically broad, measurable, and student-centered, outlining overarching knowledge, skills, or attitudes students are expected to develop. They serve as a roadmap for the course’s overall purpose and outcomes.

On the other hand, module- or unit-level objectives are more specific and granular, focusing on what students should be able to do after completing a particular module or unit. These objectives should directly align with one or more course-level objectives and be measurable and actionable, guiding daily instruction, activities, and assessments within the module.

Ideally, module-level objectives break down the course-level objectives into manageable, focused steps, ensuring that every part of the course contributes meaningfully to the larger educational goals.

Example:

Course-level outcome:

- Apply marketing techniques to small business challenges.

Module-level objectives:

- Describe key factors in marketing decisions.

- Explain five effective marketing strategies.

Assessments

Assessments determine how you will observe student abilities described in your learning objectives. For example, if a student must “define,” “identify,” or “classify,” then a multiple-choice quiz would be appropriate for these skills in remembering, understanding, and applying. However, if students are to “examine,” “critique,” and “construct,” they might write a scientific literature review to demonstrate these skills in analyzing, evaluating, and creating.

If your course is already developed, you can use a reverse approach to review existing assessments and determine which verbs best represent the skills applied for that work.

As you think about, develop, or reverse-engineer learning objectives and assessments, take a spin on this Interactive Bloom’s Taxonomy Wheel (Stony Brook University), which includes verbs, assessments, teaching strategies, and subject-matter examples.

Resources

- Anderson, L. & Krathwohl, D. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: a revision of Bloom’s taxonomy. New York. Longman Publishing.

- Davis, S. (2005). Writing learning objectives: Beginning with the end in mind. Presented at Ohio University.

- Mager, R. (1962). Preparing objectives for programmed instruction. San Francisco, CA: Fearon Publishers.

- Writing learning outcomes. (2010). British Columbia Institute of Technology. Retrieved from https://www.bcit.ca/files/ltc/pdf/ja_learningoutcomes.pdf

Want to Explore More?

For more in-depth help with writing learning objectives, DELTA is here to assist you!

- Complete a self-paced WolfSNAPS course on writing learning objectives.

- Request a 1:1 Instructional Consultation with DELTA.

- Apply for a Course Mapping Express Grant to create learning objectives and align objectives with instructional materials, activities, and assessments.